Most recent podcasts first:

Most recent podcasts first:

On reading all Jane Austen’s novels in quick succession:

At the beginning of January 2025 I decided to read all six of the main novels of Jane Austen, whose 250th birthday falls later this year (on December 16th). I began with Mansfield Park (MP), continued with Pride and Prejudice (PP), Emma (E), Sense and Sensibility (SS), Northanger Abbey (NA), and concluded with Persuasion (P). Although I had previously read all of them, some several times, I had never read them close together. Several things stood out for me as a result:

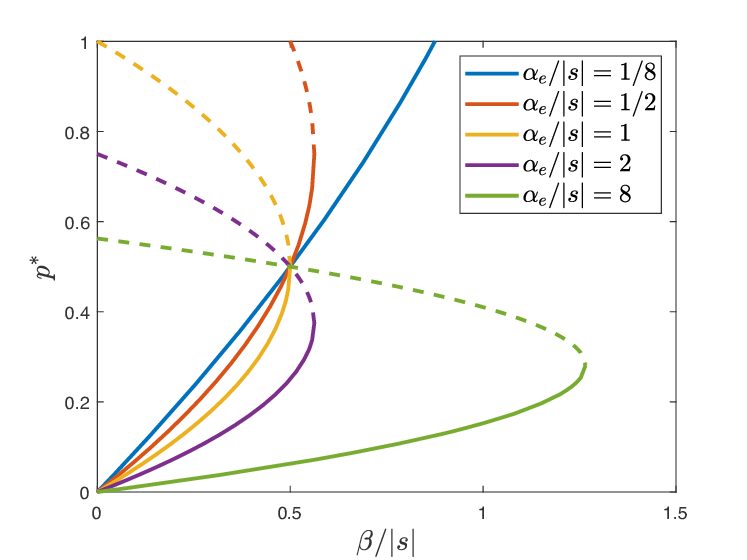

Sergey Gavrilets and I have a new paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. You can find it here.

Abstract:

People and cultures differ in the extent to which they view the world as a zero-sum environment (where one person’s gain is another’s loss) or a positive-sum environment (where certain actions can benefit everyone). These beliefs shape individuals’ willingness to work, invest, collaborate, or show hostility toward out-groups, and accept or reject various social policies. We model dyadic interactions in a heterogeneous population where individuals biased toward a zero-sum worldview are more likely to invest in competition, while those biased toward a positive-sum worldview are more likely to invest in cooperation. The environment alternates stochastically between cooperative and competitive states. Without social influence, the more accurate worldview yields higher utilities and spreads throughout the population. However, assortative matching by bias can favor the positive-sum worldview even if a positive-sum environment is somewhat less likely. With peer conformity, inaccurate worldviews can persist after a structural change in the environment, leading to cultural evolutionary mismatch. In the presence of cultural authorities who can alter beliefs, either both worldviews can coexist or one excludes the other. Moreover, when assortative matching and conformity interact, authorities may profit by amplifying individuals’ biases, creating enclaves of similarly biased people who can pay the authorities enough to make investment in persuasive technology economically viable. Cultural evolutionary mismatch is more likely in cultures marked by strong peer conformity and high responsiveness to authority when the authority promotes a suboptimal worldview. This study demonstrates how real-world conditions, peer influence, and authority interventions can perpetuate or shift zero-sum and positive-sum worldviews-at times leading to inaccurate beliefs.

In a nod to the renewed sexiness of the subject of trade policy, the BBC has re-broadcast my ten-part series from 2018, with a new final episode broadcast on 2nd May. Details here. The episodes will be available for at least a year after they go out.

This page will direct you to the themes of my current research. Some themes have pages of their own, in particular:

Research on the economics of religion here.

Research on behavioral decision making here.

Research on gender, networks and marriage markets here.

In addition I am working with Guido Friebel on the medical science of ageing and its relationship to the organisational economics of selecting, motivating and retiring leaders.

I am working with Sergey Gavrilets on the evolution of zero-sum worldviews. We have a new paper published in PNAS.

My Google scholar page is here.

Book events:

AALIMS conference in Princeton, 11th April 2025.

The book was published by Princeton University Press on 14th May 2024. It was long listed for the FT/Schroders Business Book of the Year Award 2024, and was a finalist in the 2025 PROSE awards of the Association of American Publishers.

Here is a contribution to PUP’s Ideas page to mark the release: “A sermon from a mountebank? Religious messaging in the age of AI“.

Here is an extract in Foreign Policy: “The Divine Marketplace is Pretty Crowded”.

Here is an extract in The Milken Institute Review.

Launch events were held at the University of Glasgow on 28th May and at the London School of Economics on 29th May. The lecture at the LSE was recorded, and is available on YouTube here.

I discussed the book on 11th June during the launch event for the Starling 2024 Compendium, with Harvard Business School’s Amy Edmondson.

I gave a talk in a panel at the Society for Scientific Study of Religion, Annual Meeting, Pittsburgh, 18th October 2024, with the excellent David Hollinger.

I gave the Score Strand III Lecture at the University of Cambridge on 17th November 2024, and have given book talks at the University of California at Berkeley, Chapman University and the University of Texas at Austin.

I published a piece on 30th August in IAI News entitled “How Religion Wrote the Playbook for Big Tech: Studying Religion from the Outside In“.

Reviews, podcasts and interviews are available here.

The announcement page is here, and you can order it there are well.

You can also order it on Amazon here.

Details of the French translation are here.

The data files for the Statistical Appendix are available here.

If you want to propose a review, or alert me to one that has appeared and that is not mentioned on this page, you can contact me here.

Books of the year (or books of the season) lists:

FT/Schroders Business Book of the Year Longlist.

Forbes’ 10 Best Business Books of 2024.

London Business School Best Books of 2024.

Martin Wolf’s Summer Reading for 2024.

PROSE awards 2025 of the Association of American Publishers.

Reviews and interviews:

In English:

1) By Sascha Becker, review in the Journal of Economic Literature:

“[A]n insightful and enjoyable read. [Seabright’s] platform view makes for a fresh look at religious organizations. I suspect that all scholars of religion economics will find the book equally insightful. For those less familiar with the economics of religion, the book is also an easy-to-read launchpad to the field. . . it will enthuse broad-minded social scientists as well. Finally, since the book addresses ‘big questions’ in an accessible and engaging style, it will also be of interest to nonspecialists.”

2) In The Economist – “God™: an ageing product outperforms expectations”:

“The Divine Economy looks at how religions attract followers, money and power and argues that they are businesses—and should be analysed as such.

Professor Seabright calls religions “platforms”, businesses that “facilitate relationships”. (Other economists refer to religions as “clubs” or “glue”.) He then takes a quick canter through the history, sociology and economics of religions to illustrate this. The best parts of this book deal with economics, which the general reader will find enlightening.”

3) By Jane Shaw, in The Financial Times – “Is religion just like business?”:

“A wide-ranging book, full of fascinating examples from the world’s many religions…Using his economist’s tools to analyse the lasting power of the world’s religions, Seabright has produced an engaging and insightful book, which I found myself pondering long after I had read the last page. Religion is a powerful force in many parts of the world. The religions that continue to be successful in a rapidly changing environment, he concludes, keep evolving to remain so.”

4) By Martin Wolf, in The Financial Times‘ Best summer books of 2024: Economics:

“Seabright has a great talent for addressing original questions. In this book, he reverses the familiar trope that religion is the antithesis of mere economics. On the contrary, he argues, religions are competing businesses: they attract people by providing services they value, from the mundane — a community in which to find a compatible mate — to the sublime — a sense of life’s meaning. Since these wants will not disappear, neither will religions. But, he concludes rather encouragingly, religions will fail if they choose to shackle themselves to tyrants. One hopes he is right.” See an associated DALLE image here.

5) By Shadi Hamid in Foreign Affairs: “Secular stagnation: How Religion Endures in a Godless Age”.

“The Divine Economy is an ambitious work that attempts to think economically about something that so often seems beyond the grasp of the social sciences….As Seabright puts it, “Without economic resources behind them, the most beautifully crafted messages will struggle to gain a hearing in the cacophony of life.” It is rare and even refreshing to have a book about the rise of religion that concludes, in a sense, that it’s the economy, stupid…..If there were a world in which people cared only about calculating their economic self-interest, the power of religion would be significantly blunted. But the world does not quite work that way—and, if Seabright’s analysis is any indication, it won’t any time soon.”

6) With Stephen Scott in the Starling Compendium, pp. 409-414: “An Interview with Paul Seabright”, covers both The Divine Economy and The Company of Strangers.

7) By Jonathan Benthall in The Times Literary Supplement: “The free market in faith: viewing religion through the lens of economics”.

“Combining tough-mindedness and cultural sensitivity, Paul Seabright may help to bring religion nearer to the mainstream of international political debate.”

8) By Arnold Kling in EconLib: “The Religion Business”.

There is a “tension between the narrow definition of religion and Seabright’s broader platform perspective. If religion were merely the belief in certain animal spirits, then at least in the United States we would be happy to rely on the First Amendment and a tolerant attitude of, “sure, whatever floats your boat.” But as platforms, religions have an impact on the economy, on politics, and on social relations in general. Friction would seem to be inevitable, and it becomes unclear how best to apply the First Amendment.”

9) By Atul K. Shah in The LSE Review of Books blog:

“The Divine Economy draws from the insights of sociology, anthropology, psychology, political economy and philosophy to show the deep the effect of faith in everyday life and explains why religiosity has been dynamic rather than static, and creative in response to the challenges of modernity. It shows how the prediction that secularism would prevail in an age of science and reason has been proved wrong, precisely because religion provides people with meaning, purpose and community, which secularism alone often fails to deliver. For me, religion’s scope and challenge has been truly ambitious, and the book has risen to this through a structured organisation, beautiful narratives and accessible language, authoritative open-minded research, all compiled from decades of study of the economics of religion.”

10) By an anonymous reviewer in The Interim:

“Paul Seabright, an economist at the Toulouse School of Economics, ambitiously applies not only economics but anthropology, history, philosophy, political science, psychology, science, and sociology, to understand how the world’s religions…attract and retain followers and thus money and power to sustain themselves over time. Furthermore, Seabright does so looking beyond the Abrahamic religions and all in 341 pages before landing at the statistical appendix, endnotes, bibliography, and index….Seabright is on to something when he says that secularism has not succeeded because religion provides people with meaning, purpose, and community that is not available elsewhere; even in our increasingly secular cultures, billions of people still claim (if not always practice) their faith, and examining why through an interdisciplinary lens and economic reasoning helps explain why.”

11) By Mark Koyama, on his substack:

“The Divine Economy is an original and important contribution to the economics of religion. It is accessible and readable but there is also much for specialists and scholars to discuss and debate.”

12) By Helen Nicholls for the National Secular Society: “Paul Seabright’s economic perspective on religion provides useful insights into the power of religious institutions – and how religious privilege can be countered”:

“Religious privilege exists when religious beliefs and interests are treated as more important than secular ones. Discussion of religion often rests on the presumption that it is inherently special. Paul Seabright’s new book, The Divine Economy: How religions compete for wealth, power and people, offers a different approach to religion by viewing it through an economic lens…..The Divine Economy is refreshing in that it is neither pro nor anti religion. Seabright recognises that from an economic perspective, religions operate in a similar manner to other organisations and are as susceptible to corruption and abuse as other institutions. His answer is religious organisations should be just as accountable. He is clear that the relationship between religion and the state will always present challenges that we must be prepared to face head on for the benefit of religious and non-religious people alike.”

13) By Nick Spencer in The Church Times:

“The Divine Economy is an intelligent, wide-ranging, and well-researched book offering a helpful economic lens through which to interpret religion. “

14) By an anonymous reviewer in The Times of India: “Why Religion is Big Business“:

“Paul Seabright’s The Divine Economy explores how religions function like global businesses, competing for resources and adherents. The book examines how religious authority is gained and used, and the role of persuasion versus coercion. It highlights the corporatisation of religions and its implications, emphasising the religious platforms thrive better through persuasion rather than force.”

15) By David Voas in Ethnic and Racial Studies:

“The Divine Economy is a big book, both literally and figuratively. The text alone runs to about 130,000 words, followed by 88 pages of small-font endnotes and references. The title hints at the scale of the ambition: the book amounts to a sole-authored handbook of the scientific study of religion, starting with the question ‘What is religion?’ (Ch. 1) and continuing from there….Seabright has clearly read a tremendous amount, and the scope of the work is imposing. I doubt that anyone is fully competent to assess the whole book: I confess to having little expertise on many of the issues he covers. His writing is always interesting and often persuasive, but as I find the work superficial or mistaken on the topics I know about, my confidence is reduced in his conclusions more generally.”

16) By Miguel Petrosky in The Revealer: “Winning the Religious Marketplace“:

“Seabright’s canvas of the global religious landscape is painted with subtlety; the breadth of his book is global and draws from various episodes of world history and economic thought, yet his arguments offer insights on America’s political and religious climate at this moment.”

17) By Jonathan Rée, in The New Humanist: “The business of faith“.

“Not long ago, religion seemed to be in terminal decline. But, as Paul Seabright points out in his impressive new book, it is now going from strength to strength…Seabright has done something very unusual in The Divine Economy: he has found something new to say about religion”.

18) By Lewis F. Dunlap in Business Mirror (Philippines): “The creative destruction in religion“:

“Popularized by Austrian political economist Joseph Schumpeter in his 1942 book “Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy,” creative destruction is the natural tendency in capitalism to innovate as new, better ways replace outdated ways….Creative destruction applies to religion, too. Paul Seabright, in his 2024 book “Divine Economy,” narrates the disruption in Christianity brought about by the discovery of cheaper printing in the mid-fifteenth century. Before that, the lay faithful depended on the monks who translated scriptures written in Latin. When printing became cheaper, it became possible for the lay faithful in general to privately own copies of the Bible, especially in languages that they could understand. The new, more convenient way of experiencing the scripture creatively destroyed the outdated way.”

19) By Celine Nguyen on her substack personal canon:

“The Divine Economy is honestly staggering in scope; I couldn’t do it justice in my brief Goodreads review, and I’m really just scratching the surface here! But I loved reading this book, and it’s excellent for people who love big, comprehensive, Theory of Everything reads. It’s also a book that respects rigor and respects its readers: whenever Seabright incorporates quantitative or qualitative research, he’s careful to note things like the strengths/weakness of different types of data; or competing theories of certain phenomena, and why Seabright favors one over the others.”

20) By John Lampard on the blog Theology Everywhere: “The Church Through Different Eyes”:

“There are not many books which get a review in both The Church Times and The Financial Times, but The Divine Economy: How Religions Compete for Wealth, Power and People by Paul Seabright (Princeton University Press, 2024) achieved this unusual honour…..Perhaps the most penetrating insight of the book, at least to me, is that it looks on church organisations as ‘platforms’ rather than as organisations…It occurred to me, as I read Seabright, that Mr Wesley was ahead of his time in creating a connexional ‘platform’ which was more about relationships, with travelling preachers and class leaders, rather than an organisation. A platform facilitates relationships into which people can opt in or out as they wish or as they feel the need.”

21) By Benel D. Lagua in Manila Bulletin: “Religion and Economics”:

“Seabright’s framework helps us see that religious behavior is not solely about belief but also about organizational incentives and social positioning….Seabright’s economic lens reveals that religious divisions often reflect deeper structural and organizational dynamics rather than just doctrinal differences.”

22) By Peter Passell in The Milken Institute Review (accompanying an extended extract from the Introduction):

“Seabright is not the first heavyweight economist to write about religion. The list begins with Adam Smith and includes two contemporaries of Seabright, Harvard’s Robert Barro and Ben Friedman. But he does have a unique story to tell in analyzing religions as “platform” businesses – competing organizations that succeed or fail by many of the criteria that determine the fate of organizations ranging from the owners of computer operating systems like Windows to online dating services. And did I mention that Seabright writes really, really well?”

23) By Rachel McCleary in Journal of Church and State:

“Megachurches around the globe are businesses whose primary objective is profit” is how this review begins. Given that this contradicts what is said at numerous points in the book, I asked Rachel McCleary why she had written this (she saw the book at least twice in manuscript form, and I thank her in the acknowledgments). I have not received a satisfactory reply. The review can be accessed here.

24) By Boris Begovic in Belgrade Law Review, here:

“Seabright’s book is an extraordinary, insightful, thought-provoking and enjoyable read, although reading it is not an easy task – an engaged reader is a prerequisite. The author, an economist, borrows insights from disciplines far removed from economics, especially from anthropology, history and psychology, aiming to provide a rich and honest picture of one of the most complex phenomena of human activities.”

25) By Caleb Pettit in Public Choice:

“Seabright’s platform model makes an important contribution to the economics of religion, (but) its relevance is not consistently maintained throughout the book”. Review available here.

26) By J. Robert Subrick in The Independent Review, Winter 2025/2026.:

“Religion continues to exert a powerful influence on human affairs globally. It shapes people’s preferences and influences public policy. It provides a social framework to help people form communities and supply meaning. Paul Seabright’s The Divine Economy: How Religions Compete for Wealth, Power, and People offers novel interpretations of religious behavior in the tradition of classical political economy. ….Yet, for all of its thought-provoking ideas, Seabright’s book suffers from the same problem Adam Smith had in understanding religion. Seabright approaches the topic as an engaged observer but seems unable, or perhaps unwilling, to access religion’s transcendent dimension.”

In French:

1) By Jean Duchesne in Aleteia – “En quoi la foi n’est pas étrangère aux réalités économiques”. Not so much a review as a short overview of different approaches to the use of economics to study religion.

2) With Thomas Mahler in l’Express: “Au niveau mondial, le christianisme n’est pas en déclin face à l’islam”.

3) By Bertrand Jacquillat in l’Opinion: “Plateformes numériques et religions: rivalités et concurrence”:

“Il peut paraître iconoclaste de soumettre l’espace religieux à l’analyse économique. Les religions pourtant s’y prêtent, du fait qu’elles partagent certaines des caractéristiques des organisations séculaires, et bénéficient d’une puissance financière indéniable”.

4) A short but favourable review by an anonymous reviewer in books.fr: “Les religions comme marques”.

5) By Julien Damon in Les Echos: “Les religions, des firmes comme les autres“:

“Dans le prolongement d’un Adam Smith, qui s’intéressait à la compétition des religions et à leurs relations avec l’univers politique, et à partir d’un vaste ensemble de travaux académiques, il publie un livre passionnant…Seabright réussit l’exploit, sur un sujet aussi dense, de produire un panorama, en bien des points, captivant…Cet ouvrage original et percutant, d’économie mais aussi de sociologie, mérite d’être traduit.”

This has also been republished in Telos.eu

6) By Pascal Riché in Le Monde of 21st February 2026:

“Un ouvrage foisonnant….dopé à la curiosité intellectuelle…” Full review here.

In German:

1) By Rainer Hank in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung: “Warum Religionen nicht totzukriegen sind”:

“Zwischen 1850 und 1950 erlebte der deutsche Katholizismus eine seiner größten Blüten in der Kirchengeschichte. Zufall? Nein, so lese ich es in einem faszinierenden Buch des britischen Ökonomen Paul Seabright, der an der Universität Toulouse lehrt. „The Divine Economy“ heißt das Buch. Die These: Religionen sind nicht totzukriegen. Der Forscher schreibt sine ira et studio; er argumentiert weder als Religionskritiker noch als Anwalt der Kirchen, sondern strikt als Wirtschaftswissenschaftler…..Da geht es den hiesigen Kirchen nicht anders als dem von Uber attackierten Taxigewerbe. Mehr und nicht weniger Wettbewerb, eine radikale Trennung vom Staatskirchenrecht, wäre die Empfehlung des Ökonomen für die Rückgewinnung von kirchlicher Innovation. Wer glaubt, dass es so kommt, wird selig.”

In Dutch:

1) By Aad Kamsteeg in Nederlands Daglblad: “De economie van het goddelijke: religie is naast een persoonlijk geloof ook vaak een kosten-batenanalyse“:

“Wat maakt religie zo krachtig in de levens van mensen? Is het de belofte van het eeuwige leven, of zit er óók economie in religie? De gelauwerde Britse econoom Paul Seabright bekijkt religie als een sociaal en economisch systeem dat mensen samenbrengt door de baten die het biedt.”

Other references in the print media:

1) Editorial in The Times of India: “Why Religion is Big Business: an economic lens might explain its fortunes”. Not so much a review as an editorial opinion piece that summarises (approvingly) the book’s main arguments:

“God’s work is worldly work, and religions are businesses like any other, argues The Divine Economy…”. Full editorial here.

2) By Andrew Brown in The Church Times – “Using economics to explain religion has limits”. So, apparently, does reviewing a review of the book instead of reviewing the book itself, since Brown apparently believes the author is one Paul Seagate…. My letter to the Church Times correcting the spelling is here.

3) By John L Allen Jr in The Catholic Herald: “Africa calling: Westerners must accept that Catholicism’s centre of gravity is shifting.” The article begins:

“British academic Paul Seabright recently published an intriguing new book called The Divine Economy, which attempts to offer an economic analysis of religion. For admirers of belief, it includes the consoling premise that “religion is not in decline; it is, in many ways, more powerful than it has ever been”.

To prove the point, Seabright wanted to open with a vignette to capture the enduring appeal of religious faith. It was natural, arguably even inevitable, that he chose a setting in Africa – specifically, a Pentecostal megachurch in Accra, the capital city of Ghana, where his heroine, Grace, devotes a considerable portion of her meagre income to supporting the lavish lifestyle of Pastor William.”

By Avay Shukla in The National Herald (India) on “The Disney-fication of Religion”:

“As Prof. Paul Seabright says in his extraordinary book The Divine Economy, the divine science (religion) has always had a large element of the dismal science (economics) mixed with it. It offers a product (salvation), has a network of providers (priests) and well established distribution channels. There are many ‘products’ in the market (Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism etc) and they all compete with each other for market share.

It should not surprise anyone, therefore, that the corporatisation of Hinduism now has a righteous, if not liturgical, angle to it, to serve a political purpose. It has become a bustling share market where the common investor gets his returns in divine indulgence, and the new corporates get theirs in votes. And those who do not buy into this stock market are the new kafirs.

Nietzsche had famously said that God is dead. He was wrong- God has now been repositioned as a marketable product.”

Podcasts and radio interviews:

With Rory Cellan-Jones and Iza Hussin on Crossing Channels, the IAST podcast.

With Mike Fallat on Million Dollar Stories.

With Alison Kuhlow and Roger Goldman on Mountain Money on National Public Radio.

With Chris Voss on The Chris Voss Show.

With Matthew Wilkin on The Sociology Show Podcast (video link to the episode here).

With Vivek Shankar on The Interesting Podcast.

With Louise Perry on her podcast Maiden Mother Matriarch (link here).

With Michael Shermer.

With Abhishek Ashok Kumar on The Point Blank Show.

With Richard Aedy on The Money (Australian Broadcasting Corporation).

With Julian Lorkin for the Cambridge Economics Faculty Alumni podcast.

With Morteza Hajizadeh on New Books Network.

With Thibault Schrepel on Scaling Theory:

https://open.spotify.com/episode/1Yk5JWAtB8dKwoJhamdaTW?si=m3CuQ_FfRd2EcVXqiWjxqQ&context=spotify%3Ashow%3A7o5GqRfTOzyCRABkvs6RpMhttps://youtu.be/CkQ_E-aD9fg?si=lgWkZ9zb_KxtmkMChttps://podcasts.apple.com/fr/podcast/scaling-theory/id1736309658?i=1000710389873

With Ricardo Lopes on The Dissenter:

With Johan Fourie and Jonathan Schoots on their excellent My Long Walk podcast series:

First, links to some short (one-paragraph) unpublished reviews of books I enjoyed and would recommend to at least some readers (I include here only books that stand out from the majority I read). There are only a few of these now (February 2026), but I will update them regularly as I read more.

Short reviews of recommended fiction.

Short reviews of recommended non-fiction.

Next, here are links to longer reviews I published in 2022-2025, beginning with the most recent:

David Lay Williams: The Greatest of All Plagues: How Inequality Shaped Political Thought from Plato to Marx, in European Historical Quarterly, 55(3), 2025.

Colin Mayer: Capitalism and Crises: How to Fix Them, in Society, 23 May 2025.

Charles Hecker: Zero Sum: The Arc of International Business in Russia, in the Times Literary Supplement, 9 May 2025.

Robert Eisen: Jews, Judaism, and Success: How Religion Paved the Way to Modern Jewish Achievement

“O lucky man! What poker players do and don’t have in common with plutocrats”, a view of Nate Silver’s On The Edge: The Art of Risking Everything, in the Times Literary Supplement, 22 August 2024.

“Thomas Nagel: Moral Feelings, Moral Reality, and Moral Progress”, in Society, 06 February 2024.

This is part of a symposium on Nagel’s book; the other (gated) contributions to the symposium can be found here.

“Things can only get better? The ambivalent impact of innovation on society”, a review of Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson: Power and Progress: Our thousand-year struggle over technology and prosperity, in The Times Literary Supplement, July 14, 2023.

“Trouble in paradise. Why is economic progress so little cause for celebration?”, a review of J. Bradford DeLong: Slouching Towards Utopia: An economic history of the twentieth century, in The Times Literary Supplement, 23 September 2022.

“Thomas Piketty: A Brief History of Inequality”, in Society, 31 January 2023.

“Please sir, can I have quite a lot more?”, a review of Sebastian Mallaby: The Power Law: venture capital and the art of disruption, The Times Literary Supplement, 18th February 2022.

In the academic year 2025-26 I am teaching the following courses at TSE:

In the Fall semester I am teaching:

Evolution of Economic Behavior.

Understanding Real World Organizations.

Causal Inference – jointly with Mateo Montenegro.

In the Winter semester:

Economics of Religious Competition, PhD program.

Module “The Economic Impact of Immigration”, in 2nd-year undergraduate program (in French).

Any enquiries about material for any of these courses should be directed to Paul.Seabright@tse-fr.eu.